Some time ago I placed a little article on our web site called "My Friend Fabricio". While in Bahia last month, I called Fabricio to ask him for one picture to be included at the formados' gallery at the Mestre Bimba Foundation. Immediately Dr. Fabricio Vasconcellos Soares attended my request despite his busy schedule as president of the universidade Unibahia. He told me he had several pictures with Mestre Bimba, including the ones that were published on the cover of the historical album "Capoeira Regional".

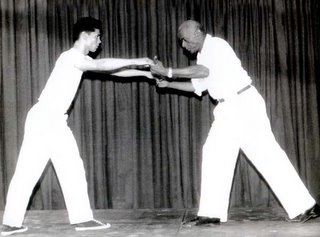

A few hours later I received one of his portraits for the gallery and a disc labeled "fotos". Only now I looked at the CD of pictures. Among them is one in which the Mestre is holding Fabricio's hands, a typical stance Bimba took while teaching the ginga. To hold the hands of the new student was one of the foundations of his Capoeira Regional. In all of the pictures, Mestre Bimba exudes his powerful persona, wisdom, and elegance.

In these times when I am so immersed into Bimba's capoeira, I could not help but becoming emotional with the photos. Thank you, Fabricio. These pictures immortalise you as the great capoeirista you were.

My Friend Fabricio.

Fabricio and I had been friends since childhood and he always was a source of inspiration for me. When Fabricio decided to do magic and charge 15 cents to the neighborhood kids for magic shows, I was his loyal assistant. When Fabricio started to study hypnotism, I too began to put all the volunteers--usually trusting old women--to sleep. When Fabricio went to business school, I went to business school. It was not a case of simple imitation, but rather a genuine affinity. One thing we did differently. Fabricio studied karate in Bahia, a pioneering venture at the time, while I concentrated on Capoeira.

Naturally, later on, Fabricio joined me in studying Capoeira, and he used to come at 5:30 in the morning to train, anxious to learn everything as fast as he could. And he learned and became a good Capoeirista. His picture is even on the back cover of Mestre Bimba's album.

What most impressed Fabricio in Karate was the picture of a Karate master with his right hand crumpling the massive belly of a bull in a deadly attack. Fabricio trained hard to perfect this movement. Cardboard, plywood, and even my mother's dearest plants could not withstand his startling attacks. Ten, a hundred, a thousand, ten thousand times he would stab his fingers into a box of sand, training tirelessly to kill a bull.

One summer day Fabricio and I were going up the Ladeira do Nordeste de Amaralina for a batizado party at Mestre Bimba's school. That batisado day, Fabricio had his big chance. On top of the Amaralina hill, he saw--not a bull, but an enormous pig eating a huge mountain of garbage. As soon as I saw the pig, I exclaimed, "Fabricio, this is it! Charge!" Fabricio looked at the animal, enthralled, but as a good Capoeirista he also noticed the crowd of brawny domino players standing by the door of a liquor store. I read his thoughts: "If I kill the pig, those guys will jump me." I didn't let him talk, saying quickly, "Don't worry, Fabricio. I'm with you. Whatever will be, will be." Fabricio had the utmost confidence in my backup in the moment of necessity. He breathed deeply, gauged the distance, and with a blood-curdling yell, flew through the air and towards the pig. It was a very powerful movement-the best he could do. With one eye on the pig, one eye on the domino players, I was frozen, goosebumps on my neck, ready for action. Fabricio's iron fingers reached the pig's belly as he roared, riveting everyone's eyes on the spectacle.

And the pig? The pig took the deadly attack to its gut without even looking at Fabricio, or interrupting its meal. Fabricio did not understand. He stood looking at his finger--and at the pig, placidly munching garbage. The domino players looked at each other and shrugged. Poor Fabricio, so much training for nothing. He never set foot in a Karate studio again.